“I feel like I’m born for this sport.”– Novak Djokovic, winner of a record 24 Grand Slam singles titles and an Olympic gold medal

“Given the same chance as others have had, blacks would dominate our sport as they have done in other sports.” – Arthur Ashe, in 1988

“You train the tennis player very similar to an N.H.L. player. In both sports, you’re talking about quick bursts of movement.” – Fitness guru Mackie Shilstone, in The New York Times

Superb physiques have long been the hallmark of tennis champions. Harry Hopman, the legendary Davis Cup captain, made superior fitness the cornerstone of the Australian men’s dynasty in the 1950s and ‘60s. As a teenager in the late 1950s, Margaret Court — the trailblazer for rigorous training in women’s tennis — became the first woman to use weights. Dozens of double-knee jumps every day, jumping rope, and two-hundred-yard wind sprints also made the Australian superstar the best-conditioned and strongest player of her era.

Bjorn Borg, the lean Swedish speedster who reigned in the 1970s, once told arch-rival John McEnroe he never got tired in a tournament match. Martina Navratilova turned into a muscular, super-fit ‘bionic woman’, as the media labelled her, and became almost unbeatable for much of the 1980s, while another Czech-turned-American star and fitness fanatic, Ivan Lendl, was renowned for his insanely gruelling off-court training. Novak Djokovic, perhaps the most dedicated and knowledgeable champion in tennis history, often talks about his ‘holistic’ approach that includes hyperbaric oxygen chambers, ‘pyramid water’, and superfoods like goji berries, spirulina, and sea algae. No wonder Men’s Health magazine’s 2021 feature about the GOAT was titled — ‘Is Novak Djokovic The Fittest Athlete of All Time?’

To learn more about the physiology of tennis athletes, I consulted Mackie Shilstone (facing page, below) one of America’s most influential fitness, wellness, and sports performance experts. The New Orleans-based author of seven health and fitness books has played a pivotal role in the success and longevity of more than 3,000 professional athletes and teams over the past 43 years. His most famous sports clients include Serena Williams, boxing champions Roy Jones Jr., Bernard Hopkins, and Michael Spinks, NFL Hall of Famers Peyton Manning and Morten Anderson, Hockey Hall of Famer Brett Hull, and baseball super-athlete Ozzie Smith. Serena won 14 of her Open Era-record 23 Grand Slam singles titles during Shilstone’s 14-year stint.

Necessary transformation: Martina Navratilova (in pic) turned into a muscular, super-fit ‘bionic woman’ while Ivan Lendl became renowned for his insanely gruelling off-court training.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Necessary transformation: Martina Navratilova (in pic) turned into a muscular, super-fit ‘bionic woman’ while Ivan Lendl became renowned for his insanely gruelling off-court training.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The sports axiom that a good big man beats a good small man is truer than ever in tennis. The top 20 men averaged 5’9” in 1973, shot up to 6’ in 1989, and now stands at 6’2.85”. Close to that average are the legendary Big Three of 6’2” Novak Djokovic, 6’1” Rafael Nadal, and 6’1” Roger Federer as well as the new Big Two of 6’3” Jannik Sinner and 6’ Carlos Alcaraz. In 2019, Reilly Opelka, a 6’11.75” American who upset Djokovic at Brisbane this January, told The Telegraph (UK) that “6’3” to 6’6” is going to be the ideal.” The women’s game has also trended taller. The top 20 now averages 5’8.6”, and players 5’9” or taller have won nine of the last 10 Grand Slam titles and the Paris Olympics. What is the best height or height range for men and women pro players?

Shilstone:There isn’t a single ‘best’ height for male and female tennis players, as success in the sport depends on a combination of factors, including skill, athleticism, strategy, and mental toughness. However, there are height ranges that tend to be more advantageous based on historical and current top players.

For men, they are as follows: The Shorter but Highly Successful Range (6’), The Ideal Balance Range (6’ to 6’5”), and The Taller Players (6’6” +). The women’s ranges are The Shorter but Highly Successful Range (5’ 6”), The Ideal Balance Range (5’7” to 5’11”), and The Taller Players (6’+).

In general, shorter players tend to rely more on speed and agility and can handle low balls better. Medium-height players offer a balanced mix of power, speed, and endurance.

Taller players benefit from greater reach and power, especially on serves, but may face challenges with movement and agility.

During parts of their careers, leading American players Mardy Fish, Lindsay Davenport, Taylor Townsend, Jack Sock, and Andy Roddick, as well as Europeans Marion Bartoli, Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova, and Jelena Ostapenko, have been significantly overweight. How does a tennis player determine their ideal weight range?

Here are the six ways to determine the ideal weight range:

1. Assess Body Composition (Not Just Scale Weight)

Lean Mass vs. Fat Mass: Tennis players should aim for a lean physique with a high muscle-to-fat ratio while avoiding excessive bulk.

Body Fat Percentage:

Men: ~8-12%

Women: ~16-22%

DEXA Scan, BodPod, or Skinfold Measurements can help assess body composition.

‘Heights’ of greatness: The top 20 men averaged 5’9” in 1973, shot up to 6’ in 1989, and now stands at 6’2.85”. Close to that average are the legendary Big Three of 6’2” Novak Djokovic, 6’1” Rafael Nadal, and 6’1” Roger Federer.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

‘Heights’ of greatness: The top 20 men averaged 5’9” in 1973, shot up to 6’ in 1989, and now stands at 6’2.85”. Close to that average are the legendary Big Three of 6’2” Novak Djokovic, 6’1” Rafael Nadal, and 6’1” Roger Federer.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

2. Consider Playing Style and Positioning

Baseliners (Endurance and Speed): Need a lighter weight to move efficiently and sustain long rallies.

Serve-and-Volley (Explosive Power and Strength): May carry a bit more muscle mass for explosive bursts.

3. Strength-to-Weight Ratio

More strength without excess weight improves acceleration and agility.

A strength test, such as relative squat/deadlift ratios, ensures enough power without slowing movement.

4. Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Needs

Players burn 800–1,500+ kcal/hour in matches.

They must maintain a sustainable weight that allows adequate caloric intake for performance and recovery.

5. Injury History and Joint Health

Carrying extra weight — even lean muscle — increases impact forces on knees, ankles, and the lower back.

A history of injuries might dictate a leaner weight to reduce joint strain.

6. Trial and Performance Data

Test different weight ranges over the training cycle, considering both the off-season and competitive season.

Use speed, agility, endurance, and recovery markers to evaluate performance.

NBA scouts and coaches tout the advantages of having a long reach or wingspan. In 2012, the average height of an NBA player was about 6’7” with an average wingspan of around seven feet. In what ways is a long wingspan an advantage in tennis?

There are four important ways.

First, a longer wingspan increases court coverage. It allows a player to reach more balls, making it easier to return shots that would be out of reach for players with shorter arms. This is especially useful in defence and when stretching for wide shots when returning serve and during baseline rallies.

Second, it helps you play better at the net. A longer reach aids in volleys and overheads, allowing a player to cover more area and put away shots more effectively. Players like 6’10” John Isner and 6’6” Daniil Medvedev use their reach well at the net.

Third, it enhances both the quality and consistency of serves. A long wingspan contributes to a higher contact point on serves, generating more leverage and power. This can help in hitting a more effective kick serves and achieving greater angles.

Fourth, it provides greater ball-striking leverage. A longer arm span can create more torque on groundstrokes, increasing shot power and spin potential.

However, longer wingspans have potential downsides. First, they generally result in a slower swing speed on groundstrokes. A longer lever arm requires more control and strength, which can make quick adjustments harder.

Second, players with a longer wingspan typically have less manoeuvrability. They may struggle with rapid hand-eye coordination for short, fast exchanges. Specifically, compact strokes are harder to execute, particularly when returning fast, swerving body serves and volleying bullet-passing shots at the body .

Net worth: A wide wingspan leads to a longer reach, which in turn helps during volleys and overheads, allowing a player to cover more area and put away shots more effectively. Players like 6’10” John Isner (in pic) used their reach well at the net.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Net worth: A wide wingspan leads to a longer reach, which in turn helps during volleys and overheads, allowing a player to cover more area and put away shots more effectively. Players like 6’10” John Isner (in pic) used their reach well at the net.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In the 2000 book, TABOO: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It, Jon Entine wrote: “Since the first known study of differences between blacks and white athletes in 1928, the data have been remarkably consistent: in most sports, African-descended athletes have the capacity to do better with their raw skills than whites.” Entine listed eight categories of “physical and physiological differences known to date” that “Blacks with a West African ancestry generally have.” The first category is: “relatively less subcutaneous fat on arms and legs and proportionately more lean body and muscle mass, broader shoulders, larger quadriceps, and bigger, more developed musculature in general.” How much do you believe these genetic advantages relate to superior tennis performance?

Genetic advantages play a significant role, roughly 55%, in superior tennis performance, but they are just one piece of the puzzle. Tennis success is a combination of genetics, training, nutrition, mental toughness, and strategy.

Here are some key genetic factors:

1. Fast-Twitch Muscle Fibres — Elite tennis players often have a high proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibres, which enhance speed, explosive power, and agility — critical for quick reactions and acceleration on the court.

2. Aerobic and Anaerobic Capacity — A strong genetic predisposition for both aerobic endurance and anaerobic power helps players maintain high energy levels throughout long matches while also executing explosive movements.

3. Height, Limb Length, and Leverage — Height and limb proportions influence serve speed, reach, and court coverage. While taller players, such as 6’11” Ivo Karlović, have powerful serves, shorter players, such as 5’7” Diego Schwartzman, typically have superior agility and baseline movement.

4. Neuromuscular Efficiency — Superior coordination, reaction time, and proprioception are often influenced by genetics. This helps players react quickly to shots and execute complex stroke mechanics under pressure.

5. Injury Resistance — Some genetic markers influence tendon and ligament strength, reducing the risk of common tennis injuries such as ACL tears, stress fractures, and shoulder issues.

6. Mental Resilience and Competitive Drive — Certain genetic factors influence dopamine and serotonin regulation, potentially affecting a player’s ability to handle pressure, maintain focus, and thrive in high-stakes matches.

Do female tennis players have some anatomical, biomechanical, and physiological disadvantages compared to their male counterparts?

They do, and that can present certain disadvantages in performance. However, these differences do not diminish their athletic capabilities but rather shape how they train, compete, and excel in their own right.

Anatomical Differences

Hip Structure: Women typically have a wider pelvis, which affects movement mechanics. This can slightly limit lateral speed and agility compared to men, whose narrower hips allow for more efficient side-to-side motion.

Shoulder and Upper Body Strength: Men generally have broader shoulders and a higher percentage of muscle mass in the upper body, providing more power in serves and groundstrokes.

Limb Proportions: Women often have a higher Q-angle (the angle at which the femur meets the knee), which can influence knee stability and increase the risk of ACL injuries.

Biomechanical Differences

Serve Speed and Stroke Power: Due to differences in upper-body muscle mass and leverage, men generally hit harder serves and groundstrokes. One of the fastest recorded women’s serves (Sabine Lisicki at 131 mph) is still well below John Isner’s record of 157 mph.

Explosiveness and Speed: Men tend to have higher levels of type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibres, contributing to quicker bursts of speed and acceleration on the court.

Grip Strength and Racket Control: Greater grip strength in men allows for better control over spin and shot variety, particularly on heavy topspin groundstrokes and when returning powerful serves or volleying high-speed passing shots.

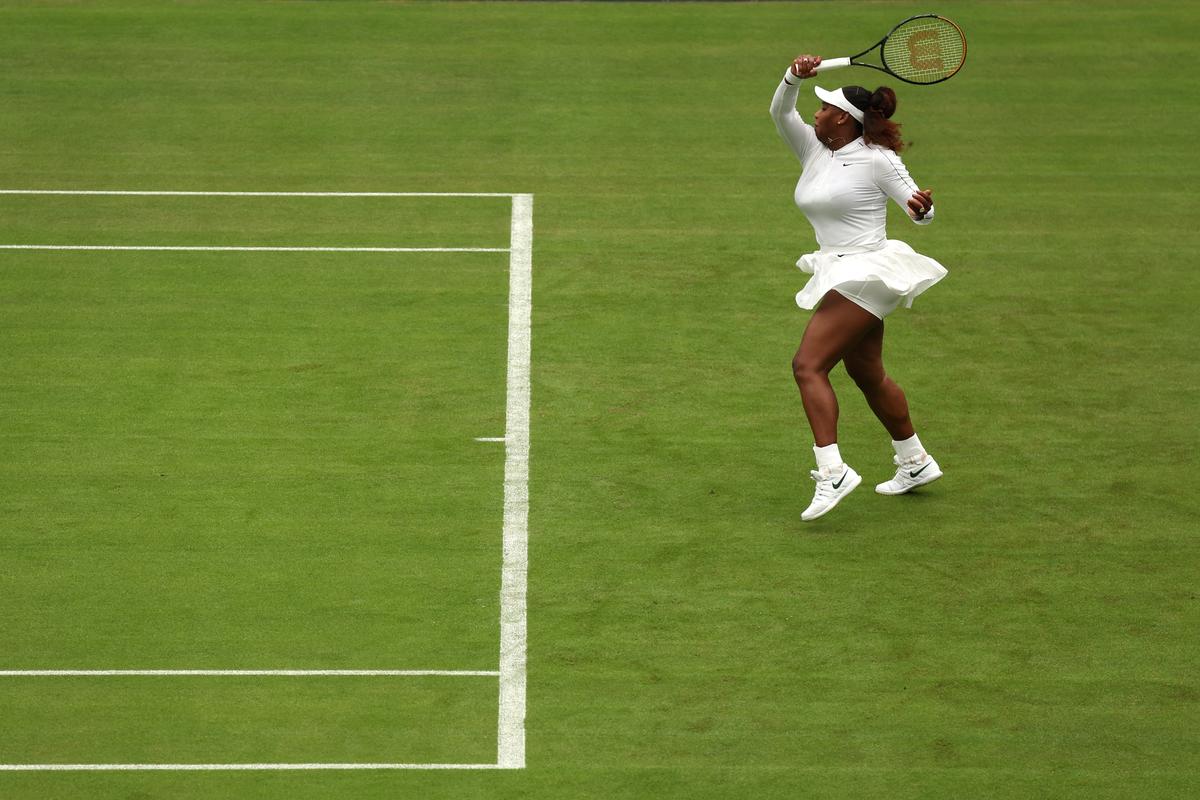

Elite female tennis players like Serena Williams have found ways to optimise their strengths, making their game just as compelling and physically demanding as men’s.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Elite female tennis players like Serena Williams have found ways to optimise their strengths, making their game just as compelling and physically demanding as men’s.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Physiological Differences

Aerobic and Anaerobic Capacity: Men have a higher VO₂ max (oxygen uptake capacity), allowing them to sustain higher intensities for longer durations. However, women are often better at endurance due to differences in fat metabolism.

Hormonal Impact: Oestrogen can lead to greater fat storage, affecting body composition, while testosterone in men promotes muscle hypertrophy and recovery.

Recovery and Injury Risk: Women have higher rates of knee injuries (e.g. ACL tears) due to anatomical and hormonal factors. However, they often show greater resilience in endurance recovery.

How Elite Female Tennis Players Adapt

Technique and Strategy: Women’s tennis emphasises angles, consistency, and court coverage rather than sheer power.

Training Adaptations: Strength training, mobility work, and biomechanical refinements help female athletes maximise their potential.

Mental and Tactical Edge: Women’s tennis often features longer rallies and more strategic point construction, requiring high levels of mental toughness and endurance.

While these differences exist, elite female tennis players have found ways to optimise their strengths, making their game just as compelling and physically demanding as men’s tennis. It’s not about disadvantages — it’s about playing to their strengths.

How much do training and environment matter?

Even with the best genetics, training, nutrition, recovery, and coaching are essential. Serena Williams (facing page, below), Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic didn’t just rely on their natural abilities — they optimised every aspect of their game through relentless work and smart preparation.

What is the remaining 45% that contributes to elite performance in tennis?

Technology, such as racquet design, weather conditions, court surface, travel schedule, and coaching quality, to name a few factors.

TRAINING METHODS OF CHAMPIONS

Besides tennis champions Novak Djokovic, Serena Williams, and Maria Sharapova, several other sports superstars have used hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT).

Maria Sharapova.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Maria Sharapova.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

They include Cristiano Ronaldo, LeBron James, Michael Jordan, Simone Biles, Lindsey Vonn, Michael Phelps, and Usain Bolt. Proven benefits for athletic performance include accelerated recovery, reduced inflammation, improved oxygen intake, increased endurance, enhanced mental focus, improved speed and power, and treatment of sports injuries.

Salt room therapy is another increasingly popular training method used by Novak Djokovic.

According to saltchamberinc.com, “Halotherapy (aka salt therapy) is a holistic therapy that involves breathing in salty air. Halotherapy is a fast-growing treatment that may provide numerous health benefits for people with respiratory and skin conditions, as well as anxiety and depression. The effectiveness of salt therapy is dependent on a halogenerator. This machine grinds particles of pure-grade sodium chloride (salt). Then, it disperses the particles into a hygienic and controlled environment known as a salt room.”

Less known in the sports world but highly effective is a machine designed for astronauts to help prevent their muscles from atrophying in zero gravity.

The use of this machine strengthened the left arm of the teenage Rafael Nadal. And that well-muscled physiological weapon — combined with his great athleticism and Western grip — created Nadal’s out-of-this-world topspin forehand, averaging 3,200 revolutions per minute and peaking at over 5,000 rpm. The greatest groundstroke in tennis history bounded viciously over and outside opponents’ strike zones and helped Rafa capture 22 Grand Slam titles.

Was it just a coincidence when the six-year world record for the indoor mile fell twice within five days?

U. S. runner Yared Nuguse set it on February 9, only for Norway’s Jakob Ingebrigtsen to eclipse it on February 14. Super spike shoes and high-tech track surfaces designed to propel runners faster than ever before partly account for this rapid record-smashing. However, a perfectly legal supplement that middle-distance runners call “Bicarb” could also explain it. Its main ingredient is sodium bicarbonate — household baking soda — which helps reduce the painful physiological effects of shorter, maximum-intensity exercise.